Defining Pan-Africanism and its Enduring

Quest for Unity

Pan-Africanism represents a profound and multifaceted

concept, fundamentally rooted in the aspiration for unity among peoples of

African heritage worldwide. At its core, it is an intellectual framework and a

global movement dedicated to the liberation of Africans and those of African

descent, particularly in opposition to European hegemony and inequitable global

systems, including racial capitalism. This foundational belief posits that

African people, both on the continent and in the diaspora, share a common

history and a common destiny. It actively champions the recognition and

celebration of African culture and heritage, while simultaneously striving to

rectify historical injustices such as colonialism and the transatlantic slave

trade. The movement’s comprehensive scope encompasses social, economic,

cultural, and political emancipation, all stemming from a deeply held

conviction in the shared purpose and collective identity of African peoples.

A critical characteristic of Pan-Africanism is its inherent

dynamism. It is not a static ideology but rather an evolving framework that

adapts to shifting historical contingencies and geopolitical landscapes. Over

the decades, its objectives have broadened significantly, moving beyond initial

calls for unity to encompass nationalism, independence, political and economic

cooperation, and a heightened awareness of African history and culture, often

emphasizing Afrocentric interpretations. This inherent capacity for adaptation

is a crucial element in its enduring relevance and longevity. The movement’s

ability to adjust its focus and strategies in response to new forms of

oppression and emerging opportunities for liberation has allowed it to navigate

complex historical periods and remain a vital force for change. Understanding

its origins, therefore, necessitates an appreciation for this foundational

capacity for evolution, which has enabled Pan-Africanism to persist and

redefine itself across centuries.

The Genesis of an Idea: Historical Context and

Precursors (15th-19th Centuries)

The deepest roots of Pan-Africanism are inextricably linked

to the profound and devastating events of the fifteenth century, specifically

the rise of European global expansion and the initiation of the transatlantic

slave trade. This brutal system, which spanned from approximately 1501 to 1867,

involved the forced abduction and trafficking of nearly 13 million African

people across the Atlantic Ocean, leaving an indelible legacy of suffering and

systemic bigotry that continues to resonate today. Portugal pioneered this

inhumane trade in the 15th century, initially through violent coastal raids

before shifting to commercial relations with African leaders, ultimately

forming military alliances to generate more captives for trade. By the 18th

century, the British had become the dominant carriers of enslaved Africans

across the Atlantic. The shared trauma of the Middle Passage and the subsequent

experience of racialized enslavement became a unifying, albeit horrific, common

denominator for a diverse array of African peoples forcibly displaced to the

Americas and the Caribbean, fostering a nascent sense of collective identity

and shared struggle.

The escalating demand for labor in the newly colonized

Americas, particularly after the catastrophic decimation of indigenous

populations, necessitated the creation of a novel human category that could be

systematically exploited. This led to the insidious invention of

"blackness" as a social construct, intrinsically linked to new power

dynamics and a negative racialized essence. In colonial territories that would

eventually form the United States, slavery became a permanent and hereditary

institution, reinforced by legal and political systems designed to codify

racial hierarchy and entrench white supremacy. The European partition of

Africa, notably formalized by the 1884-85 Congress of Berlin, directly

catalyzed the emergence of early anti-colonial movements, including the

precursor to the organized Pan-African movement, the African Association.

Pan-Africanism's origins can be traced to the earliest acts

of resistance by African people against enslavement and colonization. This

began with rebellions and suicides on slave ships, continued through persistent

plantation and colonial uprisings, and manifested in the "Back to

Africa" movements of the 19th century, notably championed by figures like

Marcus Garvey. Even when a physical return to Africa was impossible, formerly

enslaved Africans maintained the powerful idea of Africa as a homeland,

demonstrating an enduring sense of belonging and longing. The systematic

dehumanization inflicted by the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism,

paradoxically, became a unifying force. Diverse ethnic and linguistic groups

from Africa were stripped of their original identities and collectively labeled

as "Black" or "Negro" by their oppressors. This shared

experience of racialized oppression, rather than a pre-existing unity, served

as the fundamental catalyst for a nascent Pan-African identity. Pan-Africanism

thus emerged not merely as a reaction to prejudice, but as a conscious

political and cultural endeavor to reclaim, redefine, and empower an identity

initially imposed through violence and subjugation. This transformation

represents a profound act of agency, effectively reversing the colonizer's

intent and forging solidarity from shared adversity.

Intellectual and Philosophical Foundations: The

Forerunners of Pan-African Thought

The intellectual bedrock of Pan-Africanism predates its

formal organizational phase, with ideas beginning to circulate as early as the

16th century and evolving significantly through the 19th century. Early

Pan-African thought drew from philosophical traditions, including that of the

German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), who posited that

national identities were expressed through language, literature, and folk

culture, naturally leading to political union.

Several key thinkers, predominantly from the African

diaspora, laid the groundwork for the movement:

- Olaudah

Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano: These formerly enslaved individuals were

instrumental in producing early anti-slavery writings, such as Cugoano's

1791 Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery. Their works

are recognized as foundational expressions of Pan-Africanism, focusing on

ending the slave trade and refuting pseudoscientific claims of African

inferiority. Their political group, the Sons of Africa, established in

London in 1791, represents one of the earliest organizational forms of

Pan-Africanism.

- Martin

R. Delany (1812–1885): A prominent African American intellectual,

Delany was a staunch advocate for black emigration from the United States.

His 1852 work, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the

Colored People of the United States, argued that black people could

only truly flourish in a society free from white domination. Following a

visit to Africa, his Official Report of the Niger Valley Exploration

Party (1861) referred to the continent as “our fatherland” and

introduced the seminal Pan-Africanist principle, “Africa for the African

race and black men to rule them”. He is widely regarded as a key early

Pan-Africanist.

- Alexander

Crummell (1822–1898): The first African American to study at Cambridge

University, Crummell spent considerable time in Liberia. In The Future

of Africa (1862), a collection of his essays and lectures, he

articulated a vision of Africa as the motherland of the Negro race. He

contended that African Americans, exiled by slavery, had received a divine

compensation through the English language and Christianity, and thus bore

a duty to convert their ancestral continent to Christianity. Crummell, a

co-founder of Liberia College, significantly influenced W. E. B. Du Bois.

- Edward

Wilmot Blyden (1832–1912): Born in the West Indies, Blyden became a

Liberian citizen and collaborated with Crummell at the University of

Liberia. In Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race (1887), he

articulated the conviction that "each of the races of mankind has a

specific character and specific work," directly challenging the

notion of any inherent deficiency in the Negro race. Blyden's 19th-century

ideas were pivotal in propelling Pan-Africanism towards a worldwide social

movement, and he is considered a "true father" of the movement,

having extensively written about the potential for African nationalism and

self-government amidst burgeoning European colonialism.

The concept of uniting the entire “Negro” race for political

objectives was systematically developed by a diverse array of 19th-century

African American intellectuals. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) was the first

black intellectual to systematically apply Herder's theories to people of

African descent. In his influential 1897 lecture “The Conservation of Races,”

Du Bois introduced the term “Pan-Negroism,” arguing that "the history of

the world is the history, not of individuals, but of groups, not of nations,

but of races," and that each race strives "to develop for

civilization its particular message". Du Bois positioned African Americans

as the “advance guard of the Negro people,” uniquely equipped to lead this

endeavor due to their exposure to modern education.

The formal, modern phase of Pan-Africanism is generally

recognized as commencing around the turn of the 20th century. The institutional

history of this movement began with Henry Sylvester Williams, a Trinidadian

barrister residing in London. Williams played a pivotal role in establishing

the African Association (later renamed the Pan-African Association) in London

on September 24, 1897. This organization emerged partly as a direct response to

the European partition of Africa, a process formalized by the 1884-85 Congress

of Berlin. The Association's core objectives were to cultivate a sense of

unity, foster amicable relations among Africans, and advocate for the interests

of people of African descent, particularly within the British Empire's

territories, addressing the injustices prevalent in its African and Caribbean

colonies.

Building upon the African Association's foundational work,

Williams organized the First Pan-African Conference, which convened in London

at Westminster Town Hall from July 23 to 25, 1900. It is widely posited that

the term "Pan-Africanism" itself may have been coined at this seminal

gathering. The conference's central themes revolved around "Anti-racism,

self-government". It attracted 37 delegates and approximately 10 other

participants and observers from diverse regions, including Africa, the West

Indies, the United States, and the United Kingdom, with notable figures such as

W. E. B. Du Bois and Anna J. Cooper in attendance. Bishop Alexander Walters, in

his opening address, underscored the historic nature of the event, observing

that "for the first time in history black people had gathered from all parts

of the globe".

Key outcomes of this conference included the formal

transformation of the African Association into the Pan-African Association and

the unanimous adoption of an "Address to the Nations of the World."

This powerful document was subsequently dispatched to various heads of state in

regions where people of African descent were experiencing oppression.

Specifically, delegates petitioned Queen Victoria to investigate the treatment

of Africans in South Africa and Rhodesia, drawing attention to egregious

practices such as the "degrading and illegal compound system of

labour". The conference received notable coverage in major British

newspapers, including

The Times, which remarked that it "marks the

initiation of a remarkable movement in history". This inaugural congress

established a crucial precedent and laid the essential groundwork for future

Pan-African gatherings.

The consistent identification of the 1897 African

Association and the 1900 Conference as the formal inception of the organized

movement is highly significant. While earlier intellectual thought and informal

resistance existed, this period marks a critical transition from disparate

intellectual discourse and localized acts of resistance to a coordinated,

international political movement. The strategic choice of timing, immediately

following the European partition of Africa, and the location in London, the

administrative heart of the British Empire, indicate a deliberate intent to

directly confront imperial powers on their own ground and gain international

recognition. The participation of delegates from across the African diaspora

and the continent itself signifies a conscious effort to build a truly global,

unified front against shared oppression. The "Address to the Nations of

the World" and the direct petitioning of Queen Victoria demonstrate an

early understanding of the necessity for international advocacy and direct

engagement with colonial authorities, signaling a strategic shift from internal

philosophical debates to external political action and public diplomacy.

Key Early Pan-African Conferences and Congresses

|

Event/Organization |

Date |

Location |

Key Organizers/Figures |

Main Themes/Outcomes |

|

Sons of Africa (Organizational Form) |

1791 |

London, UK |

Olaudah Equiano, Ottobah Cugoano |

Early political group advocating for anti-slavery and

African dignity. |

|

African Association (Formation) |

September 24, 1897 |

London, UK |

Henry Sylvester Williams |

Established to encourage unity, promote interests of

people of African descent, and respond to the European partition of Africa.

|

|

First Pan-African Conference |

July 23-25, 1900 |

London, UK (Westminster Town Hall) |

Henry Sylvester Williams, W. E. B. Du Bois, Anna J. Cooper |

Themes: Anti-racism, self-government. Outcomes: Adoption

of "Address to the Nations," petition to Queen Victoria, conversion

of African Association to Pan-African Association. |

|

Pan-African Congress of 1919 |

1919 |

Paris, France |

W. E. B. Du Bois |

Sought reforms in colonial governance; called for greater

unity; gained publicity through endorsement by French Prime Minister Georges

Clemenceau. |

|

Pan-African Congresses (multiple sessions) |

1921 |

London, Brussels, Paris |

W. E. B. Du Bois |

Continued advocacy for African liberation and rights,

building on earlier calls for reform. |

|

Fifth Pan-African Congress |

1945 |

Manchester, England |

George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, W. E. B. Du Bois |

Pivotal shift towards explicit demands for independence;

participants encouraged to return to their countries to fight for liberation.

|

Geographical Diffusion and Early Congresses: Expanding

the Vision

While early Pan-Africanism originated primarily in the

"New World" among descendants of enslaved populations, it

subsequently diffused back to the African continent, aiming to challenge

anti-black racism on both fronts. By the early 20th century, the movement had

significantly expanded its geographical reach beyond the African continent,

establishing a notable presence in Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas. The

inaugural 1900 conference, with its delegates from diverse regions including

Africa, the West Indies, the United States, and the United Kingdom, clearly

signaled its global aspirations from its very inception.

A central figure in the movement's geographical and

ideological expansion was W.E.B. Du Bois, who meticulously organized a series

of Pan-African Congresses in key global cities such as London, Paris, and New

York throughout the first half of the 20th century. Du Bois convened the second

Pan-African Congress in Paris, France, in 1919. This gathering attracted

delegates from across the African diaspora and notably called upon the newly

proposed League of Nations to establish clear rules and codes for governing

African colonies, reflecting a burgeoning focus on international

accountability. Further sessions of the Pan-African Congress met in 1921 in

London, Brussels, and Paris, maintaining the momentum and international

dialogue.

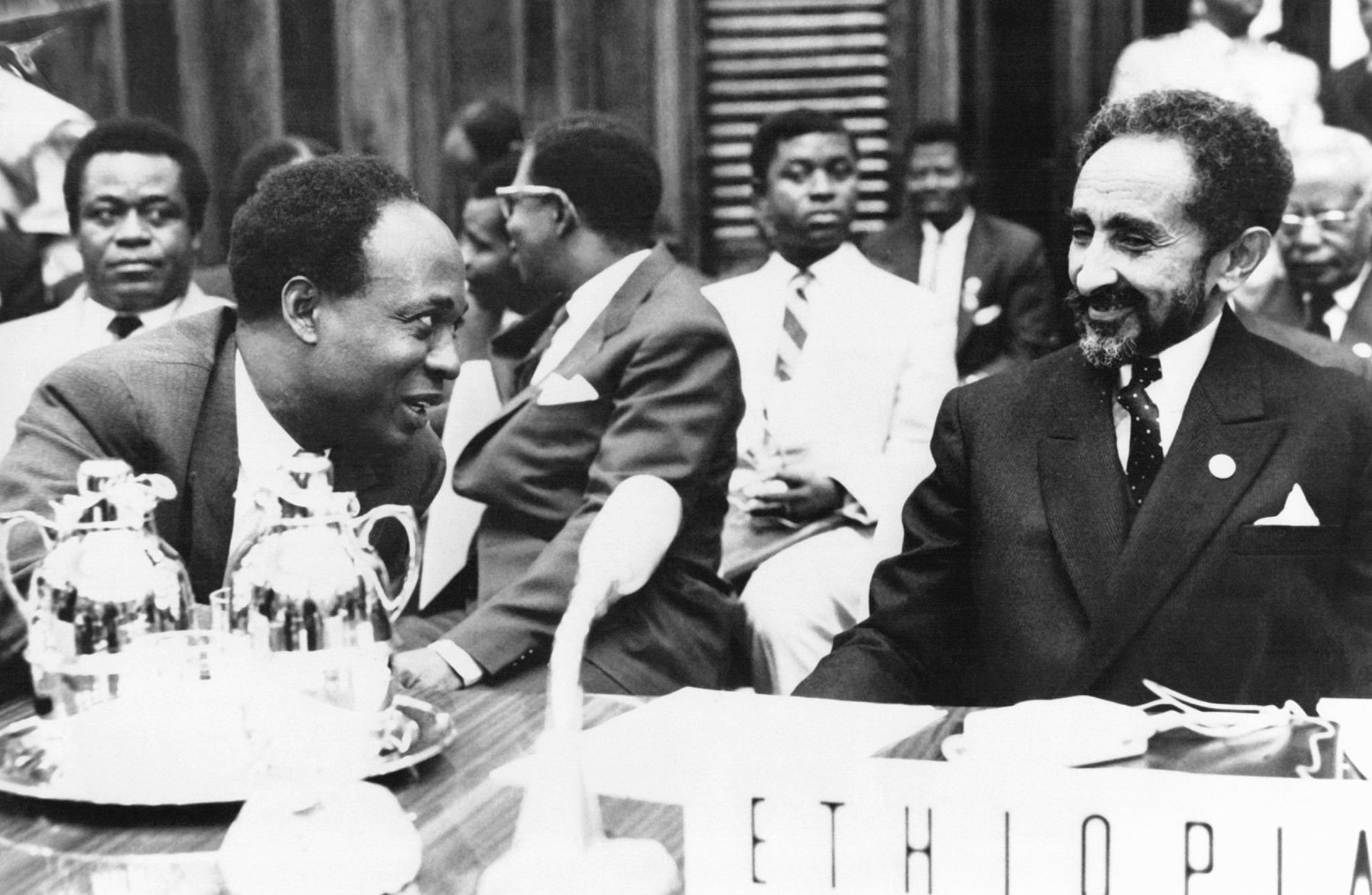

The 1945 Manchester Congress proved to be a watershed

moment, directly influencing future African leaders such as Nnamdi Azikiwe of

Nigeria and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, who would go on to lead their nations to

independence. The ascendancy of Ghana's first premier, Kwame Nkrumah, to a

leading role in the movement characterized the next stage of Pan-Africanism.

His efforts spearheaded a series of meetings that culminated in the formation

of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1960. The OAU, officially

established in 1963, aimed to advance cooperation and solidarity among newly

independent African countries and continue the fight against colonialism.

The report details a clear shift in the Pan-African

movement's focus: from early calls for colonial reform to more radical demands

for outright independence. This evolution coincides with major global events

such as the rhetoric of self-determination following World War I, the Italian

invasion of Abyssinia, and the geopolitical landscape in the aftermath of World

War II. These global conflicts and shifts in power dynamics exposed the

inherent contradictions and hypocrisies of colonial powers, simultaneously

weakening their grip on African territories. The Italian invasion of Abyssinia,

in particular, served as a potent symbol of ongoing imperialism and deeply

galvanized Pan-African sentiment, highlighting the urgent need for African

sovereignty. This demonstrates that Pan-Africanism was not an isolated

phenomenon but was deeply responsive to and strategically shaped by the broader

international political environment. The movement effectively leveraged global

crises and the changing world order to advance its agenda, transitioning from

appeals for justice and minor reforms to assertive demands for full sovereign

power and continental unity. This adaptability underscores its strategic acumen

and its capacity to capitalize on historical junctures.

VI. Early Cultural Expressions and Publications

Beyond its overt political dimensions, Pan-Africanism also

fostered significant literary and artistic projects, aiming to unite people

across Africa and its diaspora through shared cultural expression. The

Pan-African Art Movement, for instance, can be traced to the early 20th

century, emerging as African artists responded creatively to the oppressive

forces of colonialism. A pivotal cultural movement during this period was

Negritude, which emerged under the leadership of influential intellectuals and

artists such as Aimé Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Léon Damas. Negritude

served as a powerful cultural expression of Pan-Africanism, affirming Black

identity, heritage, and challenging Eurocentric cultural dominance. The

scholarly work of figures like Cheikh Anta Diop, particularly his seminal text

The African Origin of Civilization, played a crucial

role in the intellectual and cultural reclamation of African history. Diop's

critiques of contemporary racial theory and his postulate of a black African

origin for ancient Egyptian civilization contributed significantly to

dismantling colonial narratives and validating African heritage.

Significant early publications were instrumental in

disseminating Pan-African ideas. The writings of formerly enslaved individuals

such as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano, alongside the political activities

of groups like the Sons of Africa, represent foundational literary and

organizational efforts that predated the formal movement. Key intellectual

forerunners, including Martin R. Delany (

The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the

Colored People of the United States, Official Report of the Niger Valley

Exploration Party), Alexander Crummell (The Future of Africa), and

Edward Wilmot Blyden (Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race), produced

seminal texts that laid the philosophical groundwork for Pan-Africanism. W. E.

B. Du Bois's 1897 lecture “The Conservation of Races” was a critical

publication that introduced the concept of "Pan-Negroism" and

provided a theoretical framework for racial solidarity and collective

advancement. Marcus Garvey's

Selected Writings and Speeches constitute influential

works that articulated Pan-African identity and anti-imperialist sentiments.

His Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) also utilized powerful

symbolism that resonated with and was adopted by later Pan-African figures. The

existence of primary source collections such as "Black Abolitionist

Papers," "Black Drama," "African American Poetry," and

"The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association

Papers" indicates a rich and extensive textual history that documented and

disseminated the movement's ideas and expressions. The establishment of

academic journals like the

Journal of Negro History, founded by Carter G. Woodson,

further contributed to the scholarly study and widespread dissemination of

African American history, thereby reinforcing cultural awareness and

intellectual foundations crucial to Pan-Africanism.

The emergence of distinct literary and artistic movements

like Negritude, alongside the importance of publications by early

intellectuals, highlights a crucial aspect of Pan-Africanism: its cultural

dimension was not merely an aesthetic or academic pursuit. It constituted a

direct and powerful response to the colonial project's systematic efforts to

erase, devalue, or distort African history, culture, and identity. By creating

their own narratives, poetry, art, and scholarly works, Pan-Africanists were

actively engaged in a process of reclaiming and asserting a positive,

self-defined African identity. This reveals that the struggle for liberation

was fought not only on political and economic fronts but also crucially on the

cultural and intellectual battlefield. The act of reclaiming and celebrating

African heritage served as a vital source of ideological and emotional

sustenance for the broader political movement. It underscores the holistic

nature of Pan-Africanism, demonstrating its comprehensive approach to

addressing both the material and psychological dimensions of oppression and

colonial subjugation.

VII. Conclusion: A Multifaceted Origin and Lasting Legacy

Pan-Africanism's origins are not attributable to a singular

event, individual, or geographical location but rather emerged from a complex

and dynamic interplay of profound historical forces, evolving intellectual

currents, and organized collective efforts. Its deepest roots are embedded in

the brutal realities of the transatlantic slave trade and the subsequent

imposition of racialized slavery and colonialism. These experiences forged a

shared identity and a common struggle among diverse African peoples across

continents, creating the fundamental conditions for the movement. The

intellectual foundations were meticulously laid by pioneering thinkers, predominantly

from the African diaspora, who articulated sophisticated concepts of racial

solidarity, African self-determination, and the inherent dignity of Black

people, drawing upon both their lived experiences of oppression and engagement

with Western philosophical traditions. The formal, organized movement began to

take concrete shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notably in

London, through the dedicated efforts of figures like Henry Sylvester Williams

and the convening of the landmark First Pan-African Conference. From these

diaspora-led beginnings, the movement expanded geographically and

ideologically, with W.E.B. Du Bois playing an indispensable role in organizing

subsequent Pan-African Congresses that progressively shifted the movement's

focus from seeking colonial reforms to demanding full political independence.

Parallel cultural movements, such as Negritude, further solidified a collective

African identity, providing a powerful counter-narrative to the dehumanizing

and uncivilized depictions propagated by Euro-American intellectuals.

The foundational experiences of systemic oppression and the

early intellectual debates—such as the tension between advocating for a

physical "Back to Africa" return versus fighting for rights within

adopted diaspora countries—continued to profoundly shape the movement's

strategies, internal dynamics, and ideological nuances throughout its history.

The early leadership and significant contributions from the African diaspora

instilled a global perspective that remained central to Pan-Africanism's

internationalist outlook and its persistent advocacy for unity across

geographical divides. The ultimate shift towards achieving political

independence on the African continent, culminating in the formation of organizations

like the Organization of African Unity (OAU), demonstrated the movement's

remarkable adaptability and strategic success in responding to changing

geopolitical landscapes. In the post-colonial era, Pan-Africanism continues to

evolve, addressing contemporary challenges such as neo-colonialism, promoting

democracy, advocating for good governance, and fostering sustainable economic

development. The diverse and sometimes divergent origins of Pan-Africanism,

including the shared trauma of slavery, intellectual debates, the diaspora-led

organizational impetus, and the evolving aims, reveal that these early

divergences are not merely historical footnotes. Instead, they represent

fundamental questions about identity, agency, and strategic priorities that have

consistently re-emerged and continue to shape Pan-African thought and practice

across different generations and contexts. This ongoing evolution reaffirms its

enduring quest for African unity, self-determination, and a dignified place in

the global order. Understanding these foundational tensions is crucial for

comprehending the movement's rich, multifaceted, and often debated trajectory

throughout history, as well as its ongoing relevance in contemporary global

affairs.